Georgia O’Keeffe, the bellwether of American women artists, enjoyed a career that spanned more than 60 years and produced over 1,200 paintings. Borrowing terminology from German cultural critic Walter Benjamin, O’Keeffe’s works, having been perpetually reproduced in virtually ever format imaginable have lost their “aura,” the sense of awe a viewer feels when in the presence of inimitable artwork typically restricted to exhibition.

Curating the work of such an iconic artist presents an enormous challenge to a museum; the objective is to offer a fresh and imaginative look at artwork that has become not only accessible to viewers, but also wholly familiar. In order to present an original exhibition, an in-depth examination must take place into the unexplored areas of the artist’s career.

Currently on display at the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester, N.Y. through December 31, the touring show “Georgia O’Keeffe: Color and Conservation,” a collection of 27 rarely seen works, represents the efforts of art-historian Sarah Whitaker Peters and Memorial Art Gallery curator Marie Via to re-explore the career of the famous female painter.

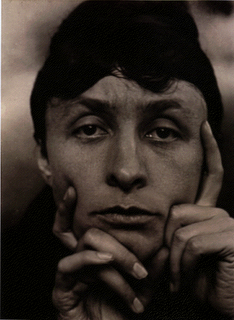

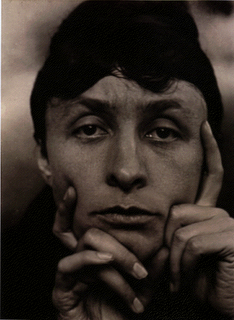

As the show’s title implies, the focus is not just on O’Keeffe’s paintings, but also on her relationship with her conservator, Caroline Keck. Peters discovered 96 letters between O’Keeffe and Keck that became the impetus for the collection. Owing thanks to Via, several photographs of O’Keeffe are also on display (on loan from Rochester’s George Eastman House). The resulting show is not a mere display of O’Keeffe’s art; rather, it is a discovery of her process and the role she played in the conservation of her legacy.

Via has hung the works in semi-chronological order, spanning four rooms in the gallery. The first room contains several photographs taken by O’Keeffe’s husband, famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The seldom seen photographs provide viewers a personal and even intimate portrait of the artist; Via ingeniously exposes the viewer to these photographs before O’Keeffe’s paintings in order to wipe clean the slate of expected familiarity one has before viewing O’Keeffe’s work.

O’Keeffe’s surroundings were often the muse for her paintings. The exhibit focuses on work from O’Keeffe’s most prolific periods: her representational period spawned from her earlier life in New York City; her move to abstraction inspired by visuals at the couple’s cabin on Lake George; and her eventual shift to surrealism triggered by Stieglitz’s death and her subsequent move to New Mexico. Via’s choice to exhibit the work chronologically has the simultaneous and remarkable effect of clustering the art by both style and location.

Where appropriate, the gallery has positioned informational plaques that contain copies of Keck and O’Keeffe’s letters and additional comments on the preservation process used for specific paintings. The plaques allow the viewers to see another new aspect of O’Keeffe – her fascinating handwriting – and also give insight into the conservation process which, done correctly, cannot be detected.

The only thing that detracts from the display is Via’s decision to place random, unattributed quotes on the walls. The viewer assumes they are quotes from O’Keeffe (and they are), but they unnecessarily clutter the walls and are unconnected to the exhibition’s otherwise strong thesis.

Ultimately, the specific paintings on display become almost inconsequential — they are less the heart of the exhibit than the work that has been put into protecting the vibrant, emblematic O’Keeffe colors. The show is a radical departure from most gallery’s treatment of O’Keeffe which often feature random assortments of O’Keeffe’s work –a sort of “here’s what we could get” display – here, a large effort has been put into casting aside the proverbial O’Keeffe and creating an innovative exhibition with a fresh focus.

Georgia O’Keeffe, the bellwether of American women artists, enjoyed a career that spanned more than 60 years and produced over 1,200 paintings. Borrowing terminology from German cultural critic Walter Benjamin, O’Keeffe’s works, having been perpetually reproduced in virtually ever format imaginable have lost their “aura,” the sense of awe a viewer feels when in the presence of inimitable artwork typically restricted to exhibition.

Georgia O’Keeffe, the bellwether of American women artists, enjoyed a career that spanned more than 60 years and produced over 1,200 paintings. Borrowing terminology from German cultural critic Walter Benjamin, O’Keeffe’s works, having been perpetually reproduced in virtually ever format imaginable have lost their “aura,” the sense of awe a viewer feels when in the presence of inimitable artwork typically restricted to exhibition.